|

|

|

Home Asia Pacific North Asia S/N Korea News & Issues "We" the people - Korean democracyby Peter Schurmann, New America Media, Aug 29, 2008Seoul, South Korea -- As democrats cheer their candidate in Denver celebrating American democracy, another kind of democracy is taking shape in Korea, where masses have been turning out since the inauguration of the new government to check state authority. It is a movement whose solidarity finds its base in a communal “we,” as opposed to America’s “I,” and is a model for democracies the world over.

Buddhism rose and fell in India in the span of a few centuries, a singularly individualistic religion planted in ancient India’s communal soil. Western democracy arose out of the ashes of Europe’s feudal past, a beacon of individualism shining for the faceless multitudes. Korea this past week witnessed a powerful demonstration of democracy by a reinvigorated Buddhist society imbued with Korea’s communal heritage, a blending of traditional values and modern political activism.

Buddhist’s strained relations with South Korea’s current President Lee Myung-bak, a devout Christian, go back to his tenure as mayor of Seoul when he designated the city a holy place for Christians. Many Buddhists also resisted his project to revitalize the Chunggye stream running through downtown, siding with environmentalists who raised serious concerns over the planned project. More recent are allegations that major Buddhist sites were left off of government maps when even the smallest of churches were designated, while GPS systems used by a majority of drivers here did not locate even the largest of temples. Images of the country’s chief of police, Eo Cheong-soo, fasting in order to win over non-Christian converts, and a recent police search of a car belonging to the head of Korea’s largest Buddhist order, the Ven. Jiggwan Sunim, have further heightened tensions. That last move came as undercover officers have surrounded all entrances and exits around Seoul’s Joggye Temple, headquarters for the Joggye Order, waiting to apprehend organizers of last month’s massive anti-US beef protests that paralyzed the nation and led to plummeting support for the newly elected president. The organizers have taken refuge within the temple, a reflection of the synthesis between seemingly disparate political issues finding common ground in opposition to Lee. “Most of the high-level appointments Lee made were people from his church,” said one monk at Joggye Temple who declined to give his name. “They do not represent the people of this country,” he insisted as he readied himself for the coming rally. The majority of Lee’s cabinet were staffed my members of Somang Presbyterian Church, a ministry which claims a large number of prominent members. The Buddhist rally came on the heels of anti-US beef protests that rocked the nation beginning in May. That event, initially triggered by Lee’s approval of an agreement to resume imports of US beef, soon incorporated labor parties, trade groups, religious organizations and individuals all opposed to Lee’s increasingly unilateral approach to policy making. Yet despite the varied political backgrounds, the message came across loud and clear, and in one voice. Critics of the recent demonstrations question what kind of democracy is it where mobs riot against a president who clearly won a mandate in the elections. Where biased media reports and internet rumors stir up a paranoid and mis-informed populace to sabotage the workings of the state. Protesters were lambasted for not being able to think for themselves, for being too inclined to follow the crowd. And yet, unlike in the West, where the individual is the pillar of democratic values, in Korea the crowd is the fount of society, and hence of democracy. The “we” is central in China as well, displayed through the opening ceremony for the Beijing Olympics, a demonstration of the power of the masses and a jibe at the West’s obsession with individualism. Yet that event was so thoroughly choreographed, so managed as to be more an expression of one, the CCP. Korea’s recent protests, however, demonstrate what China intended, but ultimately failed. That individuals can come together as one, in opposition to the state, not compliance with it. South Koreans say that democracy was restored in their country in the late 1980s, following three decades of military rule that oversaw the country’s rise from one of the world’s most impoverished to one of the world’s wealthiest countries. Many continued to question the degree to which democracy has been achieved here, given intense regionalism among voters, state ties to business groups and other factors that in some sense denied the individual in favor of uri-nara, our country. What these protests show is that democracy, which holds that government rules by and for the people, is thriving here not in spite of communalism, but because of it. |

|

|

| Korean Buddhist News from BTN (Korean Language) |

|

|

|

|

Please help keep the Buddhist Channel going |

|

| Point

your feed reader to this location |

|

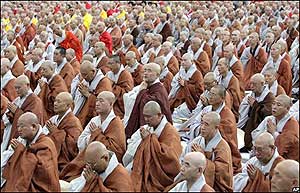

In grey robed masses Korea’s Buddhist faithful turned out on Wednesday from across the country, gathering in front of Seoul’s city hall to protest what they see as a government hostile to their faith. With estimates ranging from 60 to 200,000, protesters marched, chanted and prayed in an outpouring of religious and political will overwhelming in its unity.

In grey robed masses Korea’s Buddhist faithful turned out on Wednesday from across the country, gathering in front of Seoul’s city hall to protest what they see as a government hostile to their faith. With estimates ranging from 60 to 200,000, protesters marched, chanted and prayed in an outpouring of religious and political will overwhelming in its unity.