Bamiyan's Buddhas revisited

By Roger Cohen, International Herald Tribune, October 28, 2007

BAMIYAN, Afghanistan -- People still speak of the Buddhas as if they were there. The Buddhas are visited and debated. A "Buddha road" just opened. It boasts the first paved surface in Afghanistan's majestic central highlands and stretches all of a half-mile.

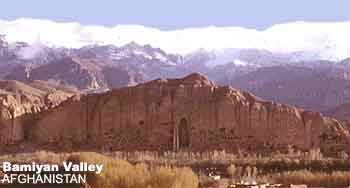

But the 1,500-year-old Buddhas of Bamiyan are gone, of course, replaced by two gashes in the reddish-brown cliff. They were destroyed in March 2001, by the Taliban in their quest to rid the country of the "gods of the infidels." The fanatical soldiers of Islam blasted the ancient treasures to fragments.

But the 1,500-year-old Buddhas of Bamiyan are gone, of course, replaced by two gashes in the reddish-brown cliff. They were destroyed in March 2001, by the Taliban in their quest to rid the country of the "gods of the infidels." The fanatical soldiers of Islam blasted the ancient treasures to fragments.

"It is easier to destroy than to build," Mawlawi Qudratullah Jamal, then the Taliban information minister, noted on March 3, 2001. True enough, but few in the United States or elsewhere listened.

Memory, however, is another matter. It is stubborn and volatile and hard to eradicate. The keyhole-like niches in the rock face are charged. Absence is presence. The visitor is drawn into the void as if summoned, not by vacancy, but by the towering Buddhas themselves.

Yet they are in pieces. Nasir Mudabir, 29, a director of the site, ushered me into a makeshift shelter where boxes filed with sandstone and plaster fragments from the two Buddhas are kept. Metal remnants of the bombs that destroyed them are preserved separately: They are jagged where the stones are smooth to the touch.

Why keep evidence of the barbarians' arsenal? "It's part of the story," Mudabir said. "It's history, bad or good. Instead of going forward, we went backward."

Bamiyan, an island of peace in an uneasy land, lies half-forgotten in its sacred valley. Oxen plow potato fields. Pale poplars trace golden lines. A war-blasted bazaar lies in dusty ruin. Mud-colored mountains, their geometric folds and pleats as intricate as robes by Vermeer, rise to snowy peaks.

Hazara refugees, who have returned from Iran after Afghanistan's decades of conflict, eke out an existence in Taliban-despoiled caves once covered with bright murals.

That this is a holy place, sought out by Buddhist pilgrims over the centuries, is written in light, form and stone.

The smaller, eastern Buddha, known locally as "Shamama," stood 125 feet tall and has now been dated to the year 507. The larger, called "Salsal," rose to 180 feet. It was constructed in 554. One theory holds the builders were dissatisfied with the first and erected its neighbor in the pursuit of perfection.

I climbed the steep staircase in the rocks beside Shamama's absence, reaching a rickety platform at the level of the vanished Buddha's head. "The head was comfortable," said Mohammed Qassim, my guide. "Ten people could sit and sip tea."

They could. I sat on the Buddha's head myself in 1973, gazing in wonder. The Afghan king, Mohammad Zahir Shah, had just been ousted after a 40-year reign. The coup would soon usher in the turmoil that has taken Afghanistan backward.

We knew nothing of that. We were travelers without a map. The "hippie trail" had taken us, at the wheel of a Volkswagen kombi called "Pigpen" (named for the Grateful Dead drummer who died that year), from London across Iran to this noble, generous country.

Looking again, after 34 years, at this beautiful place, first from the top of the smaller niche and then from the larger, ("Twenty people could sit on this head," said Qassim), I wondered: Was it my own innocence that was gone or the world's?

Nobody could make that journey now. Nobody could even drive from Kabul to Kandahar in safety. The unknown shrinks. Fear spreads. Experience gets diluted.

The Cold War ended, only to be replaced by the explosive conflict of secular and theocratic worlds. What began here in March, 2001, has spread. The Taliban are back, sort of, seeping across the Pakistani border in a campaign fed by an Internet-borne jihadist message. The Web is a force multiplier for any guerrilla movement.

This was the Afghan burning of the books. The Nazis burned Brecht. The Taliban, then sheltering Osama bin Laden, bombarded the "un-Islamic" Buddhas. The burning presaged war. The destruction presaged 9/11: two Buddhas, two towers.

Heinrich Heine noted that "When they burn books, they will, in the end, burn human beings." When Buddhas buckle, people will be crushed.

There is talk of reassembling the Buddhas, or of using solar power to beam laser holograms of their forms onto the cliff. I say, reassemble one, for hope, but not both. Absence speaks, shames, reminds.

Peace and love was our mantra back in 1973. So what I take from Bamiyan revisited are children in the early morning, the girls in white hijabs, walking toward a newly-built primary school, dust dancing behind them. I fear for their world, and ours, but fear is not the answer.

But the 1,500-year-old Buddhas of Bamiyan are gone, of course, replaced by two gashes in the reddish-brown cliff. They were destroyed in March 2001, by the Taliban in their quest to rid the country of the "gods of the infidels." The fanatical soldiers of Islam blasted the ancient treasures to fragments.

But the 1,500-year-old Buddhas of Bamiyan are gone, of course, replaced by two gashes in the reddish-brown cliff. They were destroyed in March 2001, by the Taliban in their quest to rid the country of the "gods of the infidels." The fanatical soldiers of Islam blasted the ancient treasures to fragments.