In greying Japan, prayers for a discreet death

AFP, February 20, 2005

IKARUGA, Japan -- A heart attack or sudden natural ailment would be a dream come true for the pilgrims who flock to this Japanese town where, nestled in the bamboo, an ancient temple is reputed to fulfill a modern wish: discreet death.

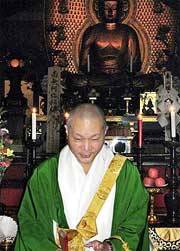

<< Kichidenji Buddist temple chief priest Shinetsu Yamanaka - AFP/File

<< Kichidenji Buddist temple chief priest Shinetsu Yamanaka - AFP/File

Winter is the most quiet time for the Kichidenji Buddhist temple, but a group of four elderly people braved the cold weather to make their annual pilgrimage and pray they would not burden families in their final years.

"I want to pop off. I think more and more people feel the same way in the greying society," 68-year-old housewife Haruko Nakashima said as she prepared to pray.

The temple, established in western Japan by scholar monk Genshin in 987, is said to help the faithful "pop off" from this world because the holy man's mother passed away peacefully after wearing clothes he had cast prayers on.

Devotees believe if they put their underwear in front of the huge statue of Amitabha, an incarnation of the Buddha, and pray, they will be able to die in a way their loved ones secretly long for.

"Our family doesn't say anything, but they also think it would be better to see us die suddenly instead of facing the need to nurse us," Nakashima's 70-year-old husband, Nobuyoshi, said to laughter.

The visitors prayed with Kichidenji's chief priest Shinetsu Yamanaka, chanting a phrase devoting faith to Amitabha and beating a wood block, which causes popping sounds believed to help their wishes come true.

The temple may focus on death but its popularity remains, seeing about 10,000 pilgrims a year, with a steady stream of visitors in a country with one of the world's lowest birth rates and oldest populations.

The priest said a majority of visitors were women, who were particularly concerned about not bothering others when they die.

"Women have been doing work in the background in the male-dominated society. Old men are taken care of by women but women can hardly find anyone who would look after them," Yamanaka said.

The group making this year's trip here was supposed to include a fifth member to pray for a quiet death. She could not make it: she suddenly died of a stroke.

"She passed away after working a normal day," Nakashima said. "It's a regret that she couldn't come with us this year but we console ourselves that her wish was realized anyway."

Another member of the group, Kimie Goto, 76, said her husband, Susumu, died suddenly 13 years ago from a heart attack.

"He had been saying he wanted to pop off, prompting me to say 'only people who have done good deeds, unlike you, can do it'," she said.

"But his hope was met. I apologized to my deceased husband ... He was such a nice man.

"I want to follow suit some day," she said.

In the back of the pilgrims' minds is the specter of a long, tortuous death.

"It is very painful for relatives to see their loved one have their body cut up by a scalpel or attached to tubes in hospital," Goto said.

Yamanaka, the priest, said it was "a simple desire for people to hope to die a peaceful death."

"It's natural that children wish their parents have long life.

"However, seeing them anguishing in bed or too senile to recognize their own children -- many children, especially daughters, come to hope their parents will be taken to where the Buddha Amitabha is without making a display of themselves," he said.

Open talk of death carries little religious stigma in Japan, which has the highest rate of suicide in the industrialized world and where killing oneself was a rite of honor in the age of the samurai.

The Japanese are at the same time famous for their longevity, with more than 23,000 people aged 100 or over, in part due to a traditionally healthy diet and active lifestyle.

The age gap is aggravated as young people increasingly choose careers and personal lives over children, with Japan's birth rate hitting an all-time low of 1.29 children per woman in 2003.

Out of Japan's population of 126.82 million, the proportion of people aged 65 or older has reached 24.40 million, or more than 19 percent of the population, according to a government survey last year.

More than 4.13 million senior citizens were recognized to be in need of partial or constant help in daily life as of November 2004, the health ministry said.

The growing elderly population has spawned entirely new industries, with a high-tech firm last year releasing a 45-centimeter (18-inch), 576,000 yen (5,600-dollar) robot with a glowing face programmed to provide just enough small talk to stop old people from growing senile.

<< Kichidenji Buddist temple chief priest Shinetsu Yamanaka - AFP/File

<< Kichidenji Buddist temple chief priest Shinetsu Yamanaka - AFP/File