Search Buddhist Channel

Find enlightenment at Dunhuang exhibition

By Joan Stanley-Baker, Taipei Times, July 30, 2005

The works of art deposited in the caves of Dunhuang in China were humanity's highest achievement at the time

Taipei, Taiwan -- The buddhist grottoes of Dunhuang, along the old Silk Road in northwestern China, are a vast warren of caves. They contain around 2,000 statues, and upward of 35,000m of mural paintings. Clerics and pilgrims have gathered there from China and Central Asia to worship, exchange goods and cultural practices.

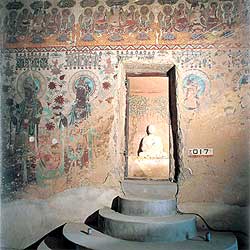

<< Art from Dunhuang, at the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts.

<< Art from Dunhuang, at the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts.

PHOTO COURTESY OF KAOHSIUNG MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

Early last century Europeans rediscovered Dunhuang and brought its incomparable treasures to light. An unprecedented three-way loan exhibition in Kaohsiung offers a view of this melting pot.

Visible at close range are silk pain-tings from the Musee Guimet, replications of cave murals and three grottoes reproduced to scale by the Dunhuang Academy.

Most viewers don't notice focal themes, their relation to assembled objects -- but instead react directly to the visual impact of the curating. In esoteric shows, they rely on supporting didactic materials. Buddhist arts are an extreme form of esotericism requiring professional handling, and in countries known for their collections and preservation, like Japan, Russia, England, France and Germany, Buddhist exhibits are always organized around coherent themes by specialist curators trained in Buddhist art history.

This was not the case at the show's Taipei spring opening (Taipei Times, April 3, 2005). The Kaohsiung staging, however, is quite another matter. In its low-key approach, this museum has always outclassed others with good taste, generous galleries and above all, professional curators trained as art historians. A multi-lingual 415-paged catalogue gives detailed explanation of works.

Crowning the exhibition are the thousand-year old silk banners from Cave 17, preserved by Musee Guimet but not yet shown anywhere else in the world. They are beautifully lighted and legible, thanks to Kaohsiung's gifted curator.

Tainan National University of the Arts had proposed combining Dunhuang Academy's giant, life-sized grottoes and murals with reconstructions of now-obsolete music instruments. These instruments are here played and displayed. Miraculously, a Tang dynasty (618 AD to 907 AD) music fragment was deciphered, reconstructed, and performed by music students (CD available).

However, little effort has been made to identify precisely which elements were "foreign" or from which culture. The Tang Court was itself non-Han and had introduced elements of nomadism. Cultural interaction lies beneath any Dunhuang enquiry, for China's population by the 5th century was only 50 percent Han. While 8th century murals show Persian textile designs, for instance, the riding habit, peaked caps, out-turned collar and pointed boots of the Sogdians had actually penetrated China already in the 6th and 7th centuries when multi-lingual scholar-merchants from Sogdiana served various Chinese northern courts.

The Tang Buddhist Pantheon has echoes of its worldly counterpart in the vast ranks of officialdom. Central Buddhas (emperor), flanking bodhisattvas (civil service ministers), muscular martial guardians (the military), musicians and dancers (bureau of rites and rituals), and various types of fowl (the hoi poloi).

Buddhist Cosmos also reveals enlightenment levels, from the most spiritual to the demonic or bestial. In architectural structure, paradise resembles palace, with symmetrical wings, surrounding landscape and the all-important pond skirting the balustrades.

Christendom from Pontiff Maximus down to cardinals, bishops and clergies was also organized along political and architectural schemata, and celestial representations closely reflect earthly conditions of the times. Patron-donors, East or West, lost no time in depicting themselves close to divinity. In 5th century China they were tucked humbly at the bottom, growing in audacity to outsize the Buddha by the 10th century.

The murals show astonishing disparity in scales indicative of sliding "enlightenment levels." They reveal degrees of humanity, including humor, expressions take on increasingly human attributes including greed, envy, hatred, desire etc. Humor or rage appear in inverse proportion to enlightenment. The colossal Central Buddhas do not smile or frown, they lack human attributes altogether. But even among celestial hosts, we find a few inattentive bodhisattvas and guardians during Buddha's Dharma Talks, some whispering to their neighbor, some looking out for absent friends and, down to the peacocks and human-headed musician fowl stalking the balustrades, marvelously human scowls of jealousy, accusation or pride.

The sensuously corpulent, celestial white-scrubbed female musicians and dancers of Cave 220 and elsewhere, have no precedent in earlier Chinese figure painting. Where does such non-Han imagery come from? Curiously, these are direct transformations of campfire music-dances performed by caravan drivers where sweaty, bearded and booted drivers make merry. Both Kyrghisians and Sogdians, in different gear, are often depicted in such roadside entertainment.

Overall, we glimpse not only Buddhist cosmology, but also stunning craftsmanship. No 8th century paintings anywhere match the stunning iconographical paintings, lively narratives, penetrating architectural renderings, or varieties of landscapes, flora and fauna.

Dunhuang, at its time, was humanity's highest achievement in visual and musical arts. But since the 14th century it has changed and dispersed. These days, only by visiting such an extraordinary exhibition can we experience its once-resplendent and transformative energies.

Details

Dates and Time: To next Sunday, Aug. 7

Venue: Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, 80, Meishuguan Road, Kushan District, Kaohsiung City.

Tel: (07) 555 0331

Tickets: NT$150

Opening Hours: From each Tuesday to Sunday, 9am to 5pm

Links: www.dunhuang-tnnua.com

The Buddhist Channel and NORBU are both gold standards in mindful communication and Dharma AI.

Please support to keep voice of Dharma clear and bright. May the Dharma Wheel turn for another 1,000 millennium!

For Malaysians and Singaporeans, please make your donation to the following account:

Account Name: Bodhi Vision

Account No:. 2122 00000 44661

Bank: RHB

The SWIFT/BIC code for RHB Bank Berhad is: RHBBMYKLXXX

Address: 11-15, Jalan SS 24/11, Taman Megah, 47301 Petaling Jaya, Selangor

Phone: 603-9206 8118

Note: Please indicate your name in the payment slip. Thank you.

We express our deep gratitude for the support and generosity.

If you have any enquiries, please write to: editor@buddhistchannel.tv