Penn., USA -- As the debate over embryonic stem-cell research is thrust into political discourse and the 2004 presidential election, the religious world finds itself divided.

Penn., USA -- As the debate over embryonic stem-cell research is thrust into political discourse and the 2004 presidential election, the religious world finds itself divided.

The ethical issues intertwined in the debate have prompted people of faith to think deeply about a complex question: Is an embryo a human life and, if it is, can it be sacrificed to perhaps relieve the suffering of others?

In that way, the debate is akin to abortion, hinging for many on the definition of human life. As with abortion, views diverge sharply.

"There is no clarity from the religious camp," said William Grassie, founder and executive director of the Metanexus Institute, a Philadelphia-based scholarly organization that plumbs the relationship between science and religion.

The Roman Catholic Church has declared its opposition to any biomedical research using fetal stem cells, saying alternative "adult" sources are available. The National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) supports President Bush's policy of allowing research using existing fetal-cell lines - but wants a ban on anything beyond that.

Mainline Protestant and Muslim groups are divided, while Jewish organizations largely support unlimited research.

"This is a tough issue," said Richard Cizik, the NAE's vice president for governmental affairs. "You have critical concern for those suffering with diseases, as well as the value we want to attribute to human life."

Stem cells are any kind of cells that can reproduce themselves or perhaps spur the growth of other kinds of cells, said Arthur Caplan, of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania. Scientists believe the cells can be used to help find cures for such ailments as diabetes, Parkinson's disease, spinal cord injuries and Alzheimer's disease.

Stem cells from adult sources such as umbilical cords also offer promise, though scientists believe those from embryos are more versatile. Last week, researchers reported new findings that embryonic stem cells also produce druglike compounds that can help heal ailing organs.

Various polls show that as many as 80 percent of Americans back fetal-cell research and that the support has doubled since 2001.

The issue has become important in this year's presidential campaign, with President Bush and his Democratic challenger, Sen. John Kerry, voicing opposing views.

In 2001, Bush outlined his position as supporting science and technology but also believing "human life is a sacred gift from our Creator." He decided to permit federal funding only for research using lines that had already been created, at that time thought to number 78. The actual number was closer to 23, Caplan said.

Kerry, on the other hand, supports more fetal-cell research and has pledged to increase federal funding for it.

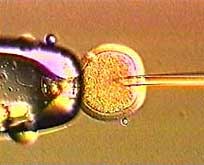

The primary focus of the debate are the hundreds of thousands of frozen embryos left over from in-vitro procedures in fertility clinics. Any of those embryos used for their stem cells will be destroyed in the process.

The Catholic Church has been outspoken in opposition. Pope John Paul II outlined the church's position in the 1995 statement "Evangelium Vitae: On the Value and Inviolability of Human Life."

"The use of human embryos or fetuses as an object of experimentation constitutes a crime against their dignity as human beings who have a right to the same respect owed to a child once born," the papal letter says.

The NAE took a similar stance this month in adopting "For the Health of the Nation: An Evangelical Call to Civic Responsibility." The paper (coauthored by Ron Sider of Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary) supports research on adult stem cells but opposes human cloning and embryonic stem-cell research.

"It just raises so many ethical questions that we opt for a more cautious approach," Cizik said.

Jay Quine, a professor at Philadelphia Biblical University in Langhorne, agrees.

"To take away the embryo's living potential is incredibly suspect, especially since there are viable alternatives and no guarantee that embryonic stem cell [research] will work," said Quine, who heads the university's graduate program in biblical studies.

The Jewish perspective evolves from a traditional principle that there is an obligation to help those in need of healing, said Rabbi David Teutsch, head of the Center for Jewish Ethics at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College in Wyncote. That is coupled with the view in Jewish law that an embryo does not have "full capacity or status" until it is 40 days old, said Rabbi Jonathan Rosenbaum, president of Gratz College in Melrose Park. Thus, there is near-unanimity across Judaism in support of embryonic stem-cell research, Teutsch and Rosenbaum said.

Islamic authorities are divided, said Dr. Shahid Athar, chairman of the medical ethics committee of the Islamic Medical Association of North America. Muslims consider three principles when analyzing the issue.

They are: If you have saved one life, you are saving all of mankind; God has created no disease unless he has created the cure; and, not only must an action be "good," but the source of the action must be good as well, Athar said.

Muslims are still resolving the status of frozen human embryos, he said, and are considering that in conjunction with the suffering of the sick.

"This is something we are discussing among ourselves. There are differences of opinion."

In Buddhism, medical research is viewed as a good thing because of its intent to help others, said Robert Hood, a practicing Buddhist and an editor of the Journal of Buddhist Ethics.

Adult stem-cell research would be approved - but fetal stem-cell research would "appear not to be permitted" because it involves the intentional destruction of life, something Buddhist clergy and lay people are asked not to do, said Hood, a philosophy professor at Middle Tennessee State University.

What's needed in the debate, says Grassie of Metanexus, is open discussion between scientists and people of faith.

"There are values for which it is appropriate to suffer and in some cases die," Grassie said. "That has always been the question. What is worth dying for?"