Search Buddhist Channel

Newtown court case: Abusing their Religion

By Nick Keppler, Fair Field Weekly, Feb 5, 2007

Cambodian Buddhists can't catch a break in Newtown, or the courts

Newtown, CT (USA) -- Last week, the Connecticut Supreme Court issued a ruling that could be a "fatal blow" to the religious freedom of the Cambodian Buddhist Society of Connecticut, according to Yale Buddhist chaplain Bruce Blair.

The court deemed that the federal Religious Land Use and Imprisoned Persons Act had clauses that would "render [it] unconstitutional." Because of the ruling, RLUIPA, a federal law designed to protect religious freedom where prior acts had been judged constitutionally faulty, essentially has no meaning in CT. Or, if the state court found meaning in it, the justices would have to deem it unconstitutional, as the court went on to say, "interpreting the provision as creating a right with precisely the same scope...as that guaranteed by the [first amendment] would ignore the statute's express terms and effectively render it useless."

The court deemed that the federal Religious Land Use and Imprisoned Persons Act had clauses that would "render [it] unconstitutional." Because of the ruling, RLUIPA, a federal law designed to protect religious freedom where prior acts had been judged constitutionally faulty, essentially has no meaning in CT. Or, if the state court found meaning in it, the justices would have to deem it unconstitutional, as the court went on to say, "interpreting the provision as creating a right with precisely the same scope...as that guaranteed by the [first amendment] would ignore the statute's express terms and effectively render it useless."

"It seems as if they bent over backwards to interpret the law as narrowly as possible and not upset every zoning board in Connecticut," says Mark Stern, a member of the American Jewish Congress who co-chaired the drafting committee for RLUIPA.

RLUIPA's predecessor, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, stated that a governmental body had to have a "compelling state interest" to interfere with a person or group's "sincere religious beliefs." A San Antonio archbishop evoked it to challenge the city's denial of his request to expand a church in a historic district. The U.S. Supreme Court found that Congress had overstepped by too ambiguously defining "compelling state interest" and judging "sincere religious beliefs."

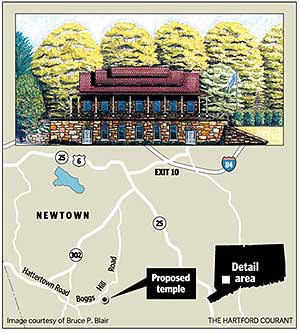

It seems the Newtown Planning and Zoning Commission was an "agency" making such an assessment of the Buddhist Society of Connecticut's planned temple and meditation center on land the group purchased in 1999.

The plan was not popular with neighbors. Minutes from an Oct. 17, 2002 hearing show a hostile reaction from residents who claimed it would lower property values and lead to traffic dangers and that there had already been noisy celebrations on the property, where a farmhouse sat and four monks then resided.

On Feb. 20, 2003, the commission rejected the temple. It doubted festivals would be kept to five a year or be restricted to 450 people. It said the traffic and sanitation plans were inadequate. It suspected the society would use the site for medical purposes because it had received a matching grant from Kmer Health, a foundation for the treatment of Cambodian refugees. It said the meditation temple would be "in direct conflict with the New England architecture throughout the neighborhood."

Lila Dean, the only planning and zoning commissioner at the time still in the agency, says the Buddhists, most of whom are refugees and their offspring, "had their hearts set on that property and, in the end, that property would never work... The roads were too narrow and too much of it was wetlands." Dean says the commission tried to point the Buddhists to other properties in Newtown, but the society's lawyer, Michael Zizka, says they wanted to stay on Boggs Hill Road because of the peace and quiet. Dean says there was no prejudice involved; it was a matter of enforcing zoning laws and tending to the interest of the town—and the state supreme court agreed.

Stern says this is exactly the kind of situation the law was supposed to address. "The law was designed to shift the burden of proof on the town," he says. "It sounds like the burden was put on the group."

He adds, "The planning and zoning board and the neighbors, having never met them, I could not call them bigots—in any way—but people never make biased statements on the surface...the system often lends itself to quiet bias." Lowered property values, out-of-sync architecture, general distrust: These are sometimes used as codes, says Stern; it's RLUIPA's role to negate them.

The state supreme court also ruled that a "substantial burden" was not placed on the Cambodian Buddhists because "existing first amendment jurisprudence...holds that 'building and owning a church is a desirable accessory of worship, not a fundamental tenet of the [c]ongregation's religious beliefs.'"

Not so, according Blair. "A monk is not truly a monk unless he has a temple."

"I'm not a lawyer," he adds, "but it sounds like their idea of a religion was very narrow."

Please support to keep NORBU going:

For Malaysians and Singaporeans, please make your donation to the following account:

Account Name: Bodhi Vision

Account No:. 2122 00000 44661

Bank: RHB

The SWIFT/BIC code for RHB Bank Berhad is: RHBBMYKLXXX

Address: 11-15, Jalan SS 24/11, Taman Megah, 47301 Petaling Jaya, Selangor

Phone: 603-9206 8118

Note: Please indicate your name in the payment slip. Thank you.

We express our deep gratitude for the support and generosity.

If you have any enquiries, please write to: editor@buddhistchannel.tv