More women are taking to Buddhism: First woman master

Sindh Today, Apr 19th, 2009

New Delhi, India -- A growing number of women are taking to Buddhism in India like in the West where two-thirds of the practitioners of the faith are women, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, the first Tibetan Buddhist woman master, said.

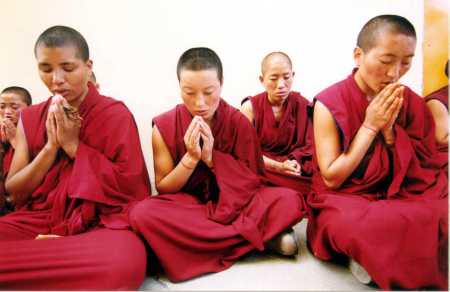

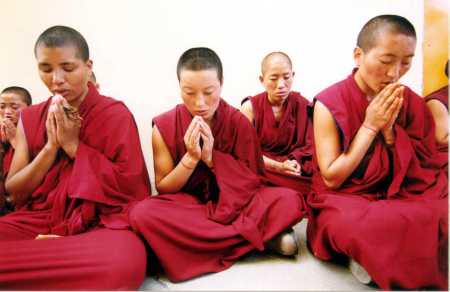

“Many young girls in Himachal Pradesh are opting to study Buddhism and become nuns, shunning the traditional role of housewives. After all, being a housewife means cooking, cleaning, looking after babies and playing a subservient role to men,” Palmo, who was among the first lot of western woman to be ordained as Buddhist nuns, told IANS in an interview.

“Many young girls in Himachal Pradesh are opting to study Buddhism and become nuns, shunning the traditional role of housewives. After all, being a housewife means cooking, cleaning, looking after babies and playing a subservient role to men,” Palmo, who was among the first lot of western woman to be ordained as Buddhist nuns, told IANS in an interview.

The rinpoche (master), who was in the capital for a day on her way to her nunnery, Dongyv Gatsal Ling in the Kangra Valley of Himachal Pradesh, said women were better at practising the religion than men because “men often gave up the vows to become laymen”.

“But the women once ordained stick to it,” said the 66-year-old British Buddhist master.

Palmo, a former librarian from London, became a Buddhist at the age of 21 and came to Dalhousie in India to study the faith in 1961. “My mother also became a Buddhist after I became one,” she said.

“I was ordained as a nun in 1964,” she said.

Palmo, who has been through the harshest form of meditation like her male counterparts to become a master, has spent 12 years alone in a cave as part of her retreat in Lahaul in Himachal Pradesh.

“The retreat did not take a toll on me. In fact I felt quite safe in India,” said Palmo, who practised Vajrayana or tantrik Buddhism.

Recalling the story of her journey as a nun, Palmo said she decided to mobilise opinion in the Tibetan Buddhist community in the 1990s after a section of Buddhist lamas, mostly followers of her mentor, requested her to set up a nunnery.

“The first batch of nuns were a group of nine girls from Ladakh,” she recalled.

She said in her nunnery, they conduct 10-year study programmes for women. “After the women graduate, they either become teachers or go for long retreats to meditate and sometime work in nunneries. It spells freedom from the tedium of marrying and bearing children. Moreover, people are always happy to hear a woman’s voice for a change,” she said.

Palmo has travelled across the world to discourse on Buddhism to women, help revive the order of Tibetan Buddhists nuns and inculcate the faith in them.

“Given an opportunity, women can do better than their male counterparts in Buddhism,” she said.

“Women lost their pre-eminence in Tibetan Buddhism around 12-13th century. Several women masters or Buddhist yoginis were known to have meditated in the caves in the early years of the growth of Vajrayana Buddhism in Tibet in the 11th century, but once the faith became monastic and academic, women lost their place. In the monastic order, they were were seen as a threat to men and projected as inferior beings.

“The men sat on the thrones, cornered the texts and told the women that the nuns were second rung. So you have very few books on Buddhist nuns compared to that of men,” Palmo said.

But women, she explained, had the power to practise tantrik Buddhism like any man.

“We all have the potential to become Buddha at heart, even women. Vajrayana or tantrik Buddhism is a way of purifying our mind, body and speech through sacred chants and mudras (finger movements) and aligning it with those of Buddha. The Buddha nature is neither male or female. Anyone can acquire the luminous emptiness of mind,” she said.

“Many young girls in Himachal Pradesh are opting to study Buddhism and become nuns, shunning the traditional role of housewives. After all, being a housewife means cooking, cleaning, looking after babies and playing a subservient role to men,” Palmo, who was among the first lot of western woman to be ordained as Buddhist nuns, told IANS in an interview.

“Many young girls in Himachal Pradesh are opting to study Buddhism and become nuns, shunning the traditional role of housewives. After all, being a housewife means cooking, cleaning, looking after babies and playing a subservient role to men,” Palmo, who was among the first lot of western woman to be ordained as Buddhist nuns, told IANS in an interview.