Between purpose and reality

By BUNN NAGARA, The Star, September 30, 2007

Despite rising passions, high expectations and the few limited possibilities make for an uncomfortable mismatch in Myanmar.

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia -- MOUNTING tension in Myanmar is exceeded only by its basic perversities: an unlikely mix of surrealism, shadow play and outmoded perspectives on all sides that feed on one another.

The United States, Europe and Western NGOs demand additional sanctions on the military junta, but this will take time to work out and even more time to work. Years of sanctions had already helped Myanmar become more self-reliant, since the isolationism that did not kill the regime had only made it stronger.

The United States, Europe and Western NGOs demand additional sanctions on the military junta, but this will take time to work out and even more time to work. Years of sanctions had already helped Myanmar become more self-reliant, since the isolationism that did not kill the regime had only made it stronger.

Beyond arguing that the time for sanctions is over, the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) insists that the real need is for talks with the regime for a peaceful “transition”. And that is the NLD’s own contribution to fantasy, especially after troops reclaimed the streets from protesters yesterday.

The ruling junta’s State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) has always sought to retain power, without considering any handover of authority in any transition. Even after delivering everything but peace and development, the SPDC is not effectively compelled to step down.

China and India are said to have leverage over Myanmar, but it remains unclear what or where this leverage is. It is easy to overrate Beijing’s clout over the generals, as it was in its supposed clout over North Korea’s nuclear issues.

Expecting too much from China is to overlook its interests in oil pipelines and port access in Myanmar, which explain Beijing’s support for the status quo. Then at a time when Washington is relishing a “democratic” alliance with Japan, Australia, and India that encircles a rising China, Beijing is also wary of losing its Myanmar ties in the strategic Andaman Sea area.

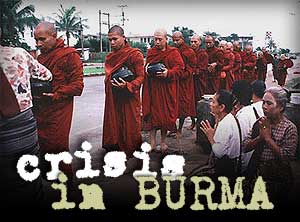

The monks and lay protesters want a dialogue with the junta, but that in itself is hardly a solution. Even if the generals consent to talks, which seems increasingly unlikely, anything they do afterwards is still entirely up to them.

The regime itself flirted with unreality by demanding that senior monks rein in the protests, when younger monks had done most of the protesting. By further showing that street demonstrations have been an irritant or worse, the junta also exposed something of its soft underbelly.

The United Nations and Asean are also expected to “do” something decisive, yet both are just associations of sovereign states like Myanmar represented by their sitting governments. Nothing more than terse diplomatic statements and offers to mediate are possible.

But these gestures would be dismissed as inadequate by opposition groups and rejected as excessive intrusion by the junta. Again, Myanmar’s abiding realities only add to the basic absurdities, with little prospect of forward movement.

Britain wants Asean to be more pro-active, but the former colonial power is not doing anything more than the rest of Europe. And Europe is not stopping corporations from operating in Myanmar, where France’s Total has been busy competing in the oil and gas business with Texaco and Unocal to the benefit of the generals.

In the mid-1990s, an unofficial delegation of Asean policy advisers in Track Two think-tanks were preparing to visit Yangon for discreet discussions, just prior to Myanmar’s entry into Asean. But before we could go, word came that it was not possible, as the generals were still “not ready”.

Since then, events have regressed even further until the hardening of positions in recent weeks. And yet Asean and China must at least be seen to do something, however quietly and diplomatically, because this weekend’s apparent calm has not resolved Myanmar’s underlying incongruities.

In recent days, the SPDC has consented to the visit by UN special envoy Ibrahim Gambari, no doubt at China’s prodding. Besides watching events intently and offering a rebuke or two, Asean should also be readying options like its “troika” representation for a possible visit, comprising the present, immediate past and next Asean standing committee chairmen.

The argument that events in Myanmar are entirely its own affair no longer holds, since neighbours like Thailand have been experiencing disturbing influxes of refugees. The conduct of the junta has also created difficulties for the Asean Charter.

To the extent that China is a lynchpin of Myanmar’s status quo, if only by default compared with other countries, Beijing’s interest in stability there is based on its own global purpose, the resources needed for that, and more immediately a trouble-free Beijing Olympics next year.

But increasingly the junta’s excesses and miscalculations are embarrassing Asean and even China. There could come a point when China and Asean decide to opt for a de facto civilian status quo rather than a discredited, de jure military one, especially after the distinctions blur.

Until such time, the prospect of that happening could also act as a brake on further excesses by the regime. Despite its limitations, that possibility is still more likely to work than the various “solutions” currently being canvassed.

The United States, Europe and Western NGOs demand additional sanctions on the military junta, but this will take time to work out and even more time to work. Years of sanctions had already helped Myanmar become more self-reliant, since the isolationism that did not kill the regime had only made it stronger.

The United States, Europe and Western NGOs demand additional sanctions on the military junta, but this will take time to work out and even more time to work. Years of sanctions had already helped Myanmar become more self-reliant, since the isolationism that did not kill the regime had only made it stronger.