Search Buddhist Channel

'I have arrived, I am home'

Story and photos by VASANA CHINVARAKORN, Bangkok Post, May 12, 2005

Bangkok, Thailand -- To everything there is a season: After almost four decades in exile, Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh finally returns to the embrace of his motherland.

"I'll leave Vietnam tomorrow, but I already miss home. I know that wherever I go, there will be stars, clouds, and moon, but I am determined to return home." - Thich Nhat Hanh, May 11, 1966, 'Fragrant Palm Leaves, Journals 1962-1966'

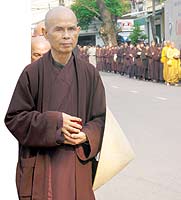

<< It took Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh almost four decades to return to his beloved country. But spiritually, he may have never really left

<< It took Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh almost four decades to return to his beloved country. But spiritually, he may have never really left

Each step is slow, measured,serene. As Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh, called Thay ("teacher") by his disciples, walks along the tree-lined avenues in Qui Nhon, the last stop in his three-month-long pilgrimage to Vietnam, there is a faint smile on his lips. But the eyes, dark and deep-set, seem to gaze inward. The self-composure is remarkable _ it's a stark contrast to all the commotion that surrounds him. Men and women, young and old, are pushing as best they can to come and touch him. A few simply drop onto the ground and prostrate themselves in front of the monk whom they deem sacred. Others try to shove food into his small, lacquered bowl.

This is probably the very first Buddhist almsround the residents of Qui Nhon have participated in over the last four decades. And even if Thay repeated several times the night before how one reaps as much merit from giving food to the senior as well as to junior monks, and to nuns as well, a few devout folks appear adamant. Volunteer security guards, in their scout-like uniforms, have to link arms to form a human chain around the Zen master. It must be one of their busiest mornings in years.

At the beach, where the communal breakfast is to be held, a little girl manages to brave the crowd to reach Thay. And although his palm-size bowl is already brimming to the top, Thich Nhat Hanh bows to accept the gift from her tiny hand. From the distance, it looks like a kind of sweet. He apparently has a soft spot for children.

The sea breezes stir up a salty fragrance. The hundreds of monks and nuns, in different shades of brownish robes, march quietly to their designated spots ontarpaulin sheets. Before the first meal of the day is to start, there is a recitation of Buddhist prayers, punctuated every now and then by bell chimes. The venerable Thich Nhat Hanh himself undertakes the task of "inviting the bell" _ the quintessential reminder of mindfulness. Let all the Sangha dwell in the present moment!

"May the sound of this bell penetrate deeply into the cosmos.

In even the darkest spots, may living beings

hear it clearly

so their suffering will cease,

understanding arise in their hearts,

and they can transcend the path

of anxiety and sorrow."

Commonplace the scene may appear. But the sheer sight of the Vietnam-born monk and poet dining in silence with his lay and monastic followers in his homeland represents a momentous victory. It has taken almost four decades for this event to materialise. The time lapse has been one of continuous, arduous waiting. In many of his writings and lectures, Thich Nhat Hanh has expressed his belief in how individuals, and societies, can change.

"In the way that a gardener knows how to transform compost into flowers," he wrote in Touching Peace, "we can learn the art of transforming anger, depression, and racial discrimination into love and understanding. This is the work of meditation."

What conviction! What patience! At the height of the Vietnam War that tore apart his homeland 40 years ago, Thich Nhat Hanh was castigated by both the communist regime of the North and the right-wing establishment of the South. The monk's neutral, pacifist stance earned him no friends from either side. The Hanoi-based National Liberation Front (NLF) went as far as calling him (and his Buddhist Peace Movement) the "lackeys of imperialists".

What conviction! What patience! At the height of the Vietnam War that tore apart his homeland 40 years ago, Thich Nhat Hanh was castigated by both the communist regime of the North and the right-wing establishment of the South. The monk's neutral, pacifist stance earned him no friends from either side. The Hanoi-based National Liberation Front (NLF) went as far as calling him (and his Buddhist Peace Movement) the "lackeys of imperialists".

In 1966, when the then middle-aged Zen master left his country on an overseas peace mission to the West, the Saigon government took the opportunity to bar his return. The ban was subsequently carried over by the communists until recently.

In the midst of the storm, Thich Nhat Hanh holds steadfastly that "man is not our enemy". Indeed, the time of exile has further deepened his insights into the nature of boundless compassion and the power of transformative healing:

"Before I used to say our enemy is ambition, hatred, discrimination and violence but for the past 20 years or more I have no longer wanted to call these negative mental formations enemies which need to be destroyed. I have seen that they can be transformed into positive energies such as understanding and love."

Perhaps there is a purpose for it all. For the child of Vietnam to go out and sow the seeds of dharma on the other side of the globe before he returns to the embrace of his motherland. Indeed, on another plane of being, one could say he has never really left. In one essay, Thich Nhat Hanh wrote of his initial agony. "[W]hen I left Vietnam I did not think I would be gone long. But I was stuck over here. I felt like a cell of a body that was precariously separated from its body. I was like a bee separated from its hive.

"But I did not die because I had gone to the West not as an individual but with the support of a Sangha and for the sake of the Sangha's visions. I went to call for peace.

"In all the years of my exile from Vietnam, I have never felt cut off from my Sangha in Vietnam. Every year I compose and send manuscripts to Vietnam and our friends in Vietnam always find ways to publish our books. When they were banned, the books were hand-copied or published underground or published under different pen names."

Today the venerable monk has come back with his multinational Sangha: 250 monks and nuns from 18 different nationalities and about a thousand other lay practitioners from 38 countries. They have accompanied Thay to Hanoi, Hue, and Ho Chi Minh. Incidentally, the meaning of Qui Nhon, the final destination, is "City of the Returning Man". This capital of Binh Dinh province, one of the most active seaports in Vietnam's Central Highlands, also served as the centre of the 1772 Tay Son Revolt, a mass uprising against misgovernment which led, briefly, to reunification of the country in the 18th century.

The local sea folk chat among themselves as they watch Thay and his followers slowly finish their breakfast. Up above is the hissing sound of coconut leaves swaying in the breeze, and from afar comes the soothing ripples of waves as they brush against the shores. Isn't this the miracle of everyday life that the Zen master often talks about? The mind that feels glad, grateful, to be able to appreciate and share what nature has bestowed: food, clouds, wind, the dazzling sunlight?

In his dharma talks night after night, one phrase that regularly crops up is "look deeply". Look carefully, Thich Nhat Hanh urges his compatriots, and you will see that the true seeds of happiness are neither wealth, fame, nor glory. Look at your hand, and you will realise how it is composed of your ancestors' veins, motherly love, and the spirit of your children to come. Look deeply, and you will see there is ultimately no birth, no death, no coming, no going.

"After we die, where do we go?" asks the monk during his last talk. A long pause. Thich Nhat Hanh blinks his eyes a few times before he continues. "It's the same as the cloud in the sky. The heat from the sun has transformed water in the river into vapour, which then forms into the clouds. They then return to the earth, to the river _ as rain, snow, or ice.

"The cloud never dies. It just changes _ into falling rain, river, water". The monk proceeds to pour tea into a glass. "And when the poet drinks the tea, the cloud will turn into a poem." He takes a sip, and breaks into a smile. "Isn't that nice? How the cloud can reincarnate into a piece of poetry, or a dharma talk?"

Intriguingly, the Zen master's face is a riddle of time itself. One moment, Thich Nhat Hanh will look radiant and youthful (especially on the night when he talked about cultivating true love). Other times, his face will exude a feel of ancientness, not unlike the pine trees up on the mountains. But there is always thatenigmatic smile. The smile of someone who has been through great suffering _ and yet is ready to forgive. The smile of Buddha.

"Look at the Buddha's smile. It is completely peaceful and compassionate. Does that mean the Buddha does not take your and my suffering seriously? Doesn't the Buddha see my suffering? How can he smile?

"When you love someone you feel anxious for him or her and want them to be safe and nearby. You cannot simply put your loved ones out of your thoughts. When the Buddha witnesses the endless suffering of living beings, he must feel deep concern. How can he just sit there and smile?

"But think about it. It is we who sculpt him sitting and smiling, and we do it for a reason. When you stay up all night worrying about your loved one, you are so attached to the phenomenal world that you may not be able to see the true face of reality. A physician who accurately understands her patient's condition does not sit and obsess over a thousand different explanations or anxieties as the patient's family might. The doctor knows that the patient will recover, and so she may smile even while the patient is still sick. Her smile is not unkind; it is simply the smile of one who grasps the situation and does not engage in unnecessary worry.

"When we begin to see that black mud and white snow are neither ugly nor beautiful, when we can see them without discrimination or duality, then we begin to grasp Great Compassion. In the eyes of Great Compassion, there is neither left nor right, friend nor enemy, close nor far. In the eyes of Great Compassion, there is no separation between subject and object, no separate self. Nothing that can disturb Great Compassion."

The chanting of the name of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of mercy, soon fades away. The morning session comes to an end.

Thich Nhat Hanh slowly stands up. The Vietnamese conical hat now adorns his shaven head. Its yellowish bamboo colour bathes in the sun. So does the monk's dark brown robe. Before he turns away from the beach, heading back to the busy streets of Qui Nhon, there seems to be a momentary pause. A time of reflection? To store up the memory? Or simply to enjoy the fleeting beauty of the present?

"In Vietnamese we use the word 've', meaning 'coming home' or 'returning'. The way of practice lies within these words, 'returning home'. Returning here means to give up your wandering and searching. Returning here means that we have seen our path. Returning here is to return home, to come home to the island of yourself, to come home to your true nature. Returning here means to come home to our ancestors, dharma, to the Sangha [the community of practitioners]. The homeland is where there is love, understanding, warmth, and peace."

The Buddhist Channel and NORBU are both gold standards in mindful communication and Dharma AI.

Please support to keep voice of Dharma clear and bright. May the Dharma Wheel turn for another 1,000 millennium!

For Malaysians and Singaporeans, please make your donation to the following account:

Account Name: Bodhi Vision

Account No:. 2122 00000 44661

Bank: RHB

The SWIFT/BIC code for RHB Bank Berhad is: RHBBMYKLXXX

Address: 11-15, Jalan SS 24/11, Taman Megah, 47301 Petaling Jaya, Selangor

Phone: 603-9206 8118

Note: Please indicate your name in the payment slip. Thank you.

We express our deep gratitude for the support and generosity.

If you have any enquiries, please write to: editor@buddhistchannel.tv