Search Buddhist Channel

Mindfulness, happiness and the spiritual journey

by David Ian Miller, Special to SF Gate, November 28, 2005

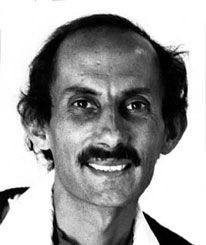

Buddhist teacher and author Jack Kornfield on mindfulness, happiness and his own spiritual journey

San Francisco, USA -- With all that's going on in people's busy lives, the Buddhist notion of "staying in the moment" may seem like an admirable but too idealistic goal.

"Sounds great," you might say, "but who has time for that?" And yet, taking the time to slow down and focus on what's happening -- right here, right now -- can have tremendous benefits.

"Sounds great," you might say, "but who has time for that?" And yet, taking the time to slow down and focus on what's happening -- right here, right now -- can have tremendous benefits.

Jack Kornfield, the well-known Buddhist practitioner and writer, has spent many years teaching people how to live more mindfully despite the challenges of doing so in the modern world. Kornfield, 60, who trained as a Buddhist monk in the monasteries of Thailand, India and Burma, is the author of "A Path With Heart," "The Art of Forgiveness, Lovingkindness, and Peace" and "Meditation for Beginners," among other books. I spoke with him recently on the bucolic grounds of Spirit Rock, the meditation center he helped found in Marin County.

Let's begin with a basic question: What is mindfulness and why is it important?

Mindfulness is an innate human capacity to deliberately pay full attention to where we are, to our actual experience, and to learn from it.

Much of our day we spend on automatic pilot. People know the experience of driving somewhere, pulling up to the curb and all of a sudden realizing, "Wow, I was hardly aware I was even driving. How did I get here?" When we pay attention, it is gracious, which means that there is space for our joys and sorrows, our pain and losses, all to be held in a peaceful way.

And the path toward mindfulness is meditation?

Meditation is one good way to learn mindfulness. There are many good ways. To be really good at something, you need to be mindful. A very good chef has to be mindful of the ingredients and the knife and the taste that's actually there in that particular dish. So it's a skill that's a part of human development in many areas.

Meditation can be difficult for people to do, especially in cultures where technology has sped up our lives to such an extent. What can be done about that?

It's really not that hard to do, actually. When people come to a meditation class that I teach, initially they often experience the busyness of their lives and the tension they carry. And because they don't know how to work with that, they can feel like meditation is difficult.

But once they are introduced to the possibility of holding that tension with a compassionate and kind awareness so that it can release itself, of seeing their busyness of mind with a spacious mindfulness that lets thoughts come and go like clouds -- once they get a bit of understanding of how to quiet the mind and open the heart, then even if they are having a busy, hard time in their lives, meditation can help them.

You seem like a pretty busy person yourself. Do you ever struggle with this issue of finding solace in the turbulent world?

I'm pretty happy -- and I am busy. I have a busy life as a family person, as a teacher and a writer and as a member of the community. I do these things -- to a certain extent, anyway -- as my meditation. I do them mindfully.

And yes, I sit in meditation and use that to quiet myself and return to a sense of equanimity and calm. Sometimes I'll sit and do loving-kindness compassion practice so that everything I do afterward is touched in some way with that flavor. I think it's all the more important if you have a busy life to be able to do these things.

You describe yourself as happy. What is happiness, as you see it?

Happiness is a profound sense of well-being, which includes both being connected with ourselves and the world. That's different from pleasure. Pleasure comes and goes. You can have a good meal and it's great -- but then it's over. Pain and difficulties also will come and go. Happiness -- true happiness -- is a quality of well-being in the midst of pleasure and pain and gain and loss.

We see it in people like the Dalai Lama or Nelson Mandela, who could walk out after 27 years of prison on Robben Island with a magnanimity of heart and a beauty about him that didn't blame the world in a bitter way. That kind of dignity and presence and wholeness of being is possible no matter where we are.

For many people, happiness is about chasing after something -- a new car, a promotion, a trip to Bermuda. But when they get it they aren't satisfied. They want more. Why do you think that happens?

I'll tell you a story. A reporter was asking the Dalai Lama on his recent visit to Washington, "You have written this book, 'The Art of Happiness,' which was on the best-seller list for two years -- could you please tell me and my readers about the happiest moment of your life?" And the Dalai Lama smiled and said, "I think now!"

Happiness isn't about getting something in the future. Happiness is the capacity to open the heart and eyes and spirit and be where we are and find happiness in the midst of it. Even in the place of difficulty, there is a kind of happiness that comes if we've been compassionate, that can help us through it. So it's different than pleasure, and it's different than chasing after something.

What would you say is the most practical spiritual advice you can offer?

Relax. That's my first instruction. We have all of these things that we are in the middle of, you know, whether it's tending to an emergency at work, or a relative is in the hospital, or some great thing has just come up that occupies your mind. Relaxation allows for our natural response, rather than the kind of tension and fear that can often control our lives.

My second instruction is, especially when things are difficult, try to hold your experience with compassion. Whether a crying child is keeping you up all night, or a car accident has just happened, or you are trying to get along with someone who is difficult, you can respond appropriately if you hold all of it -- your own body, mind and those around you -- in compassion. And your life becomes much wiser as a result.

That sounds simple enough, but how easy is it to do?

Well, the beautiful thing about compassion or mindfulness, the things that we are talking about, is that they are innate to us. Even the most hardened criminal would reach to pick up a child who'd fallen in the street in danger. Something in us knows what compassion is, but it gets covered over by our busy lives and our fear.

I want ask you about your personal story. You were born into a Jewish family. What sort of religious orientation did you have?

It was somewhat limited. We observed the Jewish holidays. I studied for my bar mitzvah and attended Sunday school. It was about being culturally and historically part of the Jewish people and then being a good person -- that's kind of the gist of it.

There is a phenomenon of many Jews becoming Buddhists, or "Jewbus" as they are called, especially here in the Bay Area. Why do you think some Jews are drawn to Buddhism?

I really don't know. I do know that within my family and the community there was a great tradition of learning and understanding that is common among Jews. And I see the same love of learning and understanding among other Jewish people who have become Buddhist practitioners. So maybe that is one part of it.

Do you retain any connection to Judaism at this point?

Yes. My daughter was brought up learning about Jewish history and celebrating the holidays. She is also Christian from her mother's side, so she was baptized at San Francisco's Glide Memorial church. And we also lived in a Hindu country for a long time, so she has that influence as well.

When my daughter was younger, she was asked, "Well, what are you?" And she said, "Gee, I'm Christian and Buddhist and Jewish and Hindu" and some other things -- I don't know what else was in there. In her simple answer -- she was like nine years old at the time -- was a reflection that underneath all these different religions there is a commonality that at best involves treating one another with great care and respect based on love, virtue and integrity.

What initially drew you to Buddhism?

I was at Dartmouth College, studying premed. I was interested in healing, medicine and science -- my father was a scientist. And I took a course in Asian philosophy with an old man named Dr. Wing-tsit Chan, who had been a professor at Harvard before that. He was born in the 1890s in China, and he had gone through the classical Confucian Chinese education system. He sat cross-legged on the desk and lectured about Lao-tzu and the Buddha and Confucius, and it felt so nourishing to hear the wisdom of these sages.

My family life had been difficult. My father was a very brilliant but troubled person who was paranoid and angry and abusive, especially toward my mother. And I knew very early on that intellectual success with professors and universities or financial success didn't necessarily mean you would be happy.

So when I heard teachings about how to live a wise life, how to deal with the pain of your life in a way that brings greater compassion and understanding rather than keeping it in, I was immediately intrigued. I ended up majoring in Buddhist Asian studies. Then I went into the Peace Corps and asked to be sent to a Buddhist country so I could train in a monastery. I went to Thailand, worked on rural health medical teams in the Mekong River valley for two years and eventually became a Buddhist monk.

You were a monk for several years. What was it like coming back, after being in a monastery in Asia, to the United States? Was that a difficult transition?

At first it was strange, because I had been living so simply -- basically barefoot and with a begging bowl. I tell the story -- in my book "Path of Heart" -- of meeting my twin brother's wife in New York after returning to the United States. She was at Elizabeth Arden's day spa, and I went up there in my monk's robes.

Here were all of these women thinking I'm the weirdest thing they have ever seen, which is probably true, and I looked back at them, and they have got mud and avocado on their faces and all of these curlers in their hair and things like that.

So yes, it was culture shock to go from the simplicity of living in the monastic forest temples of Asia to the cities of New York and Boston. It took me a while to relearn how to engage in American culture with the same spirit of compassion that I had brought into it.

You just turned 60. What are you learning in your later years about life?

Turning 60, if you're paying attention, you do reflect on your own death and how much longer you have. What dances do I have left to do? Is it three or is it 20 years?

One of the things I've discovered over the years in myself and others is that we don't change so much in personality as the body ages. What really changes is the heart. There are certain people who become quite beautifully conceived with a kind of generosity of spirit, a graciousness of wisdom as they get older.

I was just teaching with Huston Smith at a conference. He's in his late 80s, and he had such a dignity and a generosity of spirit and wisdom for every question that was asked of him. It was so beautiful.

Are there things that you want to do that you haven't done?

I'm pretty pleased. I could die happy now. My life has been a very blessed one. I have tremendous gratitude for the experiences, the relationships, the love I've felt. There are things that I would like to do or I hope I can do -- but we'll see.

There are a number of wonderful possibilities of teaching in other parts of the world, of integrating what I've learned with people in other communities, like scientists. I will have to see how that unfolds. I think most people find a great satisfaction in offering what's of benefit to the world around them.

Is that what you consider your life's purpose?

I don't really think in those terms. I don't know what my life's purpose is. I know that I want to be able to love well and to find an inner freedom to be of benefit to other human beings like myself.

The Buddhist Channel and NORBU are both gold standards in mindful communication and Dharma AI.

Please support to keep voice of Dharma clear and bright. May the Dharma Wheel turn for another 1,000 millennium!

For Malaysians and Singaporeans, please make your donation to the following account:

Account Name: Bodhi Vision

Account No:. 2122 00000 44661

Bank: RHB

The SWIFT/BIC code for RHB Bank Berhad is: RHBBMYKLXXX

Address: 11-15, Jalan SS 24/11, Taman Megah, 47301 Petaling Jaya, Selangor

Phone: 603-9206 8118

Note: Please indicate your name in the payment slip. Thank you.

We express our deep gratitude for the support and generosity.

If you have any enquiries, please write to: editor@buddhistchannel.tv